Blue Angels ‘Diamond’ Epitomizes Team’s Contract of Trust

Blue Angels ‘Diamond’ Epitomizes Team’s Contract of Trust

(Courtesy of Aviation Week & Space Technology/McGraw-Hill)

William B. Scott, Pensacola, Fla. — Nov 13, 2006, p. 48

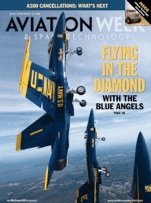

The 2006 air show season marks the U.S. Navy Blue Angels flight demonstration team’s 60th anniversary. Known for dynamic, precision flight maneuvers in close proximity, the team’s pilots live by an almost-mystical credo that permeates the entire Blue Angels squadron. Rocky Mountain Bureau Chief William B. Scott was invited back for a second flight with the team–this time in the four-ship Diamond formation–providing a close-up look at the Blue Angels’ formula for breeding perennial excellence. A special thanks goes to film producer James Cross, who made the initial introductions and suggested the theme for this report.

Headed for the Naval Air Station Pensacola main runway, six U.S. Navy F/A-18 Hornets taxi past their ramrod-straight ground crews. Two of the sleek blue-and-yellow fighters turn toward one end, while the other four break off, taxiing to the opposite end of Runway 07R.

Four Hornets that constitute the Blue Angels’ Diamond formation ease into position, with aircraft No. 1 stopping just left of the runway centerline. Cdr. Stephen (Boss) Foley flies that F/A-18, leading the Navy’s official aerial demonstration team. He’s also the Blue Angels squadron commander.

Slightly behind and to Foley’s left, No. 3, flown by Lt. Cdr. Thomas (Duck) Winkler, slips to within feet of No. 1’s wing. The other wingman (No. 2), Lt. Cdr. Anthony (Opie) Walley, stops on Boss’s right. The Slot pilot, Maj. Matthew (PWOC) Shortal (No. 4), positions his jet echelon-right, slightly aft and outboard of Walley’s. This Aviation Week & Space Technology editor is strapped into the aft cockpit of Shortal’s two-seat F/A-18B today.

Chief Warrant Officer-3 Todd (MO) Herbert, the Blue Angels’ Maintenance Officer and ground-to-air communicator, clears the flight for takeoff: “Boss, MO! Updated winds are 060 at six. We own the airfield and the airspace! You’re cleared for takeoff! Have a good one!”

The Blue Angels’ four-aircraft basic formation flies the Diamond 360, a constant-altitude turn, maintaining 12-18-in. separation. Credit: PH2 RYAN COURTADE/BLUE ANGELS PHOTOS

Foley acknowledges and addresses his four-ship flight in a barely understandable blur of upbeat commands: “Boss! We’re cleared for takeoff! Winds are 060 at six–a left headwind. Check your parking brake off! Get your trim set! Check nosewheel steering ON! Maneuver: Diamond Half-Cuban Eight! Here’s to walkin’ on the Moon!”

The latter is a nonstandard addition today, a quick salute to Apollo astronaut and fellow naval aviator Capt. Eugene A. Cernan, who is listening via headset. Cernan is standing next to MO Herbert at the Blues’ communications cart, near the squadron’s hangar, accompanied by Lt. Cdr. Tarah (Doc) Johnson. The team’s flight surgeon, she doubles as the ground-based quality control officer, grading each Blue Angels maneuver for postflight review during the flight’s debriefing.

The other three Diamond pilots respond in quick succession, using callsigns:

“Opie!”

“Duck!”

“PWOC!” (pronounced “pe-walk,” a term Shortal rarely explains.)

Boss: “Let’s run ’em up! Smoke . . . ON! Off Brakes . . . NOW! Burners Ready . . . NOW!” Shortal waits a second, then shoves our Hornet’s twin throttles forward, into afterburner. All four aircraft are accelerating down the runway, still in tight formation. At a predetermined speed, noses come up and the jets break ground. Shortal radios “Gear!” and four sets of landing gear and flaps retract in unison.

Immediately, Walley (No. 2) and Winkler (No. 3) slide into position, locked on Foley’s right and left wings, respectively. Shortal (No. 4) presses full left rudder, adds a bit of power and slides into the slot position, his F/A-18’s nose tucked beneath Boss’s tail and sandwiched between the two wingmen. Aggressive use of rudder instead of ailerons for this type of position adjustment makes sure the Diamond’s four aircraft maintain the same wing angle.

Easily able to count rivets in the Hornets’ aluminum skins now, I’m struck by how incredibly close to each other these pilots are flying. I’m also surprised by the degree of relative movement within the formation. From the ground, the Diamond looks rock-solid, each jet welded into position in relation to the other three. But not up here. Above my head, Walley’s wingtip-mounted missile-launcher rail constantly wags up and down several inches–but never remotely threatening an unintentional tap of our canopy. Occasionally, our Slot jet inches a bit higher, and I hear Boss’s engine exhaust rumble across our canopy and feel it tickle the F/A-18’s twin tails, setting up a mild airframe vibration. Shortal eases downward a touch and the noise and vibration disappear.

Complex maneuvers such as the Fleur de Lis begin with all six Hornets breaking in different directions. Seconds later, they rejoin at a higher altitude, creating a flower-shaped smoke pattern. Credit: PH2 RYAN COURTADE/BLUE ANGELS PHOTOS

I’d heard the words and observed myriad outward signs during ground operations, but here, with 18-24 in. separating these four fighters as they climb vertically in tight formation, I begin to fully understand. This is the manifestation of a DNA-deep Blue Angels credo. This is Trust and Confidence. And while it may appear magical to a viewer on the ground or in the backseat of No. 4, it’s the fully expected outcome of a well-defined and -structured process rooted in rigorous training.

“IT’S LESS OF A STATED CONTRACT with one another that ‘I’ll be here and you’ll be there,'” Foley explains later. “We take time to painstakingly [train] everyone, going through a building-block approach to develop a degree of proficiency. Trust and confidence manifests through development of skill sets and proficiency.”

The F/A-18s come out of afterburner, still climbing straight up, then all four pilots gently pull over the top, inverted. “Smoke . . . ON!” and four noses soon point at the ground, the formation rolling to smoothly complete the Half Cuban Eight from takeoff–a signature Blue Angels maneuver that’s typical of this team’s aggressiveness.

“We come out of the gate with guns a-blazing,” Shortal later quips. “As soon as we take off, we’re in show mode.”

The Diamond levels off, then immediately explodes in four directions. “This year, for the first time, we do a breakout maneuver at the bottom of the Half Cuban Eight,” Shortal explains. “Nos. 2 and 3 break right and left, Boss pulls up and I do a slight unload, so it looks like the Diamond breaking apart. We rejoin behind the crowd as the Solos come down the runway for takeoff.”

Blue Angels Nos. 5 and 6 are the demo team’s “Solos,” which perform a series of two-aircraft maneuvers. High-speed opposing passes involve 800-1,000-kt. closure rates. Credit: PH2 RYAN COURTADE/BLUE ANGELS PHOTOS

Throughout each Blues demo, Lead Solo pilot Lt. Cdr. Ted (Bunza) Steelman and Opposing Solo Lt. Cdr. John (J.B.) Allison alternate maneuvers with the Diamond, often flying directly at each other from opposite directions and passing in front of the crowd. They, too, put their lives in each other’s steady hands and good judgment, protected only by that mystical Trust and Confidence element.

“When J.B. and I make opposing passes, we’re looking at 800-1,000-kt. closures and [cross] 25-75 ft. apart,” says Steelman, a second-year Solo pilot. “That may sound like a big separation, but it’s really, really close at that kind of closure [speed]. There’s no reaction time.”

Allison is in his first year as Opposing Solo, but earned his Blue Angel spurs as

the 2005 airshow narrator and news-media demonstration pilot. I flew with Allison in February 2005, and can attest to his precision-piloting skills (AW&ST Mar. 21, 2005, p. 50).

The Solos build trust the same way the Diamond pilots do–via repetitive, step-by-step, progressive training, until each profile is 100% solid and predictable. During the Blues’ 10-week winter training cycle at Naval Air Facility El Centro (Calif.) the Solos “do what we call ‘drills down the line.’ I fly [below] and behind J.B. [during] the Knife Edge maneuver. He rolls to 90-deg. [bank] and holds it. We do that hundreds of times, before we ever approach each other head-on,” Steelman says. “We’re doing 400 kt., but I don’t want to see his altitude change by 5 ft. and his lateral displacement by 5 ft., maximum. [From behind,] I watch him do the Knife Edge roll-in, the inverted roll-in and the four-point roll-in over and over, and give him real-time feedback: ‘A little too much g. Little too much cancel.’

“It’s just mechanics, but when it comes time to do a [head-on] pass with me, I don’t even think about whether he’ll pull just a hair too much positive-g that might create closure [of the distance] between us. So, that trust and confidence is hammered out early in the season, through very mechanical, repetitious drills. And J.B. trusts me to always be predictable, whether it’s the comm cadence, a clearing maneuver–whatever.”

Once the Solos are airborne, we sweep back before the crowd in the Diamond 360–a banked, constant-altitude turn in very tight formation. Shortal slides halfway up No. 2’s wing, until our canopy is directly under the F/A-18’s wing-fold line. No. 3 edges in until Shortal and I are sandwiched tightly between the two wingmen. “And we’re tight!” Shortal later emphasizes. “That way, it looks like a diamond from the ground,” with our displaced position under No. 2’s wing compensating for the crowd’s ground-to-air parallax. Over the years, the Blues have reduced such minute adjustments to a science, ensuring the desired “look” is presented to a crowd on the ramp.

Shortal’s and my helmets now are about 18 in. below No. 2’s left wing. If the canopy weren’t there, I could stand up and grab the Hornet’s missile rail. “The 360 maneuver is the tightest set we fly,” Shortal notes. “Our separation depends a lot on environmental [factors]–how bumpy it is–and our proficiency. If we’re really rockin’ and rollin’, we should be flying 18 in.–if not down to 12 in.–apart on certain maneuvers.”

Next up is the Diamond Roll, another Blues trademark. Entering from crowd-right, Foley calls, “OoooooK!” On the “kay,” he starts a slow left roll and all four Hornets roll with him, wings perfectly aligned. Shortal eases the control stick to the left, while feeding in a lot of right rudder.

“We try to match up wings,” says Shortal. “So, on the left, No. 3 puts in a little left stick, then starts feeding in right rudder to make sure we don’t get what we call ‘curl’–mismatched wing angles.” Shortal monitors Boss’s roll rate and estimates the minimum altitude the formation will be at during the “out” part of the maneuver. If necessary for a safe exit, he calls, “Speed the roll.”

IN QUICK SUCCESSION, interspersed by the Solos’ dazzling dual-aircraft maneuvers, we perform the Diamond Aileron Roll and the Diamond Dirty Loop, the latter with all four Hornets’ landing gear down. Shortal, in enthusiastic, pumped-up terms, later describes the brain-rattling Aileron Roll: “Boss calls for a slight pullup, and each pilot pulls up, saying to himself, ‘one potato, two potato,’ then unloads the gs. Boss calls, ‘Ready, HIT IT!’ and WHAM! I go full left stick, rolling at 1g.” Each pilot checks his alignment to ensure no over or under banking, Shortal calls “Take it in,” and Foley commands, “Smoke OFF!” as the formation tucks back into a tight Diamond.

We set up for what Shortal says is the most challenging maneuver of the demo for a Blues Slot pilot–the Diamond Double Farvel. The two wingmen slide outboard, giving the No. 1 and 4 jets room to maneuver. On Foley’s command “Set . . . Roll it in!” both Foley and Shortal roll inverted. No. 2 and 3 remain upright, still in formation. Our half snap roll throws me violently side to side. Somehow, Shortal and I now are flying upside down, with our jet’s nose halfway up No. 1’s belly. “Boss” is also inverted, between us and the nearby Pensacola runway. We stay that way for a good 20 sec., streaking past the crowd at constant altitude.

“Anytime we roll, we use full stick deflection, so we all match [rates],” Shortal explains. “Boss and I align with the horizon, I call ‘Take it in,’ make sure everybody’s safe, then call ‘Smoke ON!’ The Double Farvel is the most challenging maneuver in the demo for a Blue Angel Slot pilot. It’s the coolest, but also the hardest, maneuver I fly. You’re hanging in the straps, and it’s hard to reach the controls. It’s just not intuitive. The Navy and Marine Corps never train to fly inverted, on top of another guy. It took a lot of practice and patience to learn.”

Here again, I’m aware of an almost palpable Trust and Confidence these two pilots are exercising. “When I flip upside down for the Double Farvel and fly up close to Boss, I’m not looking at airspeed, altitude–nothing,” Shortal continues. “I’m focused on Boss, looking right down at his [engine] intakes, trying to stay 2 ft. above his jet, holding a nice, stable platform. It’s easy to get into a PIO [pilot-induced oscillation] there, so I just concentrate on being smooth and holding it.”

The margin for error in this maneuver is razor-thin. Our twin vertical fins are very close to No. 1’s exhaust blasts, and any bobble can get exciting. “I’ve hit Boss’s jet wash before, and that’s not fun,” Shortal admits. “A consistent Boss is the secret. He has to set a solid platform, and I have total trust and confidence that he’s going to keep it nice and level.”

Shortal radios, “A little push,” and pulls the throttles back a smidgen to separate us from the No. 1 Hornet. Foley commands a left snap roll to bring Nos. 1 and 4 upright, the formation tightens up and we swing behind the crowd. Shortal calls “Ease it out,” and the Diamond’s interaircraft separation widens, giving each pilot a few moments to relax. This is extremely demanding flying, and nobody could tolerate an entire demo in tight formation. It’s too mentally and physically draining.

The Double Farvel maneuver calls for Boss and the Slot aircraft to roll inverted, while the two wingmen remain upright. Credit: PH2 RYAN COURTADE/BLUE ANGELS PHOTOS

The Double Farvel maneuver calls for Boss and the Slot aircraft to roll inverted, while the two wingmen remain upright. Credit: PH2 RYAN COURTADE/BLUE ANGELS PHOTOS

The Slot pilot then eases forward, so he’s just above No. 1’s belly (inset). Credit: PH2 RYAN COURTADE/BLUE ANGELS PHOTOS

The Slot pilot then eases forward, so he’s just above No. 1’s belly (inset). Credit: PH2 RYAN COURTADE/BLUE ANGELS PHOTOS

Steelman later characterizes the intensity and energy demands of a Blues demo, comparing it with a carrier landing: “Navy pilots say flying the ‘ball’ takes 40 sec. of absolute, intense focus to bring your airplane aboard ship and catch the No. 3 wire. But the [Blue Angels] demo is 40 min. of absolute, intense focus. If you stray mentally for just a moment, it’ll have repercussions, no matter how good you are or what position you’re flying,” he stresses. “And anytime a deviation happens. . . . I tell you, it makes the hair on my neck stand up. We like things to stay the same. Otherwise, we wouldn’t feel comfortable flying only inches apart and cruising along, upside down, at 200 ft. above the ground.”

The Right-Echelon Fan maneuver, the Left-Echelon Roll (LER) and the Line-Abreast Loop follow in quick succession. “That whole sequence–the Fan, LER and Line-Abreast Loop–is the hardest set we do as a Diamond,” Shortal explains. “They come right in a row–three maneuvers that really require us to be on our game.”

The Loop is done as a five-aircraft formation, all the Hornets in a straight, horizontal line. “It’s very difficult,” Shortal says. “It’s just not intuitive to fly wingtip-to-wingtip, about 10 ft. apart, looking down your shoulder.”

I see Steelman join on our right, then Foley, his cadence slow and steady, calls: “Up . . . we . . . go!” Five jets start a 2.6-2.8g pullup, maintaining about 420 kt. Foley calls, “Adding power . . . adding power.” We’re climbing vertically now, and all five sets of wings appear to be strapped to the same invisible plane. “We try to match wings, making only small corrections,” Shortal says later. “If you get a little tight on the other jet, you just breathe on a little rudder. Aileron [movement] would make it too hard to fly on each other.”

Over the top, and we’re now pointed at the ground. Trust and Confidence are hard at work here. Five fighters accelerating toward terra firma and only Foley is paying attention to airspeed and altitude readouts on his head-up display. Down the backside of the loop, speedbrakes come out to slow us down, and Boss calls for the next setup. In a fluid ballet, the Diamond slips back into formation, but Steelman is now nestled directly below and behind our No. 4 Hornet, in what the Blues call the “Stinger” position. We race down the show line, then No. 5 breaks out to set up for the Solos’ Opposing Horizontal Rolls maneuver.

The Diamond wheels behind the crowd, preparing for the Vertical Break. We move into a stacked, trail position, each successive fighter’s nose under the tail of the jet ahead of it. In the lowest (No. 4) position, I’m looking up at No. 3’s tail hook–about 5 ft. above me–and Nos. 2 and 1 are above No. 3. Shortal positions our Hornet fore and aft so he can barely see No. 3’s leading-edge flaps.

Back in front of the crowd, the stacked formation starts a climb. Shortal calls, “Go Diamond,” and all four aircraft shift to their familiar four-point formation. Then the Diamond breaks apart again–Foley pulls over the top, continuing a loop. No. 2 breaks 90 deg. right, rolling to inverted, and No. 3 does the same to the left. Shortal pushes over to about -0.5g, then snap-rolls left to a 90-deg. bank and pulls 7.5g in a body-crushing, 180-deg. arc that culminates as a rendezvous with the other three jets back at show-center.

Despite an intense anti-g straining maneuver to combat the g-forces–tightening leg, abdomen and torso muscles for all I’m worth–my vision still shrinks to a small tunnel, then the world turns gray. Eyes are wide open, but I can’t see a thing; only a blank gray screen. Blood’s being g-pulled from my cranium and retinas, immediately degrading my vision. I keep straining, breathing in short, quick bursts, but I’m on the verge of passing out. Voices and engine noise sound far away, a sure sign I’m on the verge of the world fading to black. Those 7.5gs seem to last forever. I dearly wish I had a g-suit helping me, but the Blues don’t wear them. The chaps-like g-suit’s inflation with each onset of g-forces would move a Blues pilot’s right arm–which rests on his leg, for leverage–and that’s unacceptable. Such tiny arm movements would translate to uncommanded stick inputs and, in turn, unwanted aircraft responses.

“WHEN I FLY PEOPLE [in No. 4’s backseat], they can’t believe how many gs we pull–and how fast our rendezvous are,” Shortal comments, soothing my bruised, damn-near-passed-out ego. “You have the negative, then positive, push-pull effect . . . and a 180-deg. turn, so the gs just keep coming. These level rendezvous are really about pushing the ‘I-believe’ button, too.” Trying to regain my senses, I barely notice the rendezvous, and am annoyed at the g-tolerance of youthful Blues pilots.

After rejoining, the Diamond resets for another series of high-g maneuvers–the Tuck-Under Break, Barrel Roll Break and the Low Break Cross. The first is “really Trust and Confidence. No. 2 and 3 are doing blind, 90-deg. break turns at 7.5g, and Boss breaks hard left, [also] pulling 7.5g,” Shortal recaps later. “We’re all trusting each other to roll out on the right heading.” That’s an understatement. If someone screws up here, some blue-and-yellow aluminum’s going to get seriously scratched and dented.

The Barrel Roll Break is another test of one’s g-tolerance, which again underscores how physically fit these pilots have to be. “Coming straight at the crowd, Boss pulls up,” Shortal explains in a rapid-fire litany. “We come over the top, then roll to parallel the show line. At the bottom, Boss calls, ‘Ready . . . Break!’ [Nos.] 2 and 3 pull 6.5-7g, at 25 deg. nose-up, and I [No. 4] flip inverted and fly down the line upside down. At the smoke-off point, [Nos.] 2 and 3 reverse to join on Boss. I do a 270-deg. tuck-under break, then a hard, 7.5g break left. That’s a tough one. I’m hanging in the straps, inverted, at 200 ft. above the runway. WHAM! I come hard left for about 120 deg., roll out, go full afterburner, reverse at 5.5-6g in order to rendezvous and set up for the Low Break Cross–a new maneuver we added to the high show this year.”

Over the top of a loop, the Diamond points at NAS Pensacola’s runways. At times, only one pilot in the formation can monitor airspeed and altitude; the safety of the other three depends on him. Credit: PH2 RYAN COURTADE/BLUE ANGELS PHOTOS

Over the top of a loop, the Diamond points at NAS Pensacola’s runways. At times, only one pilot in the formation can monitor airspeed and altitude; the safety of the other three depends on him. Credit: PH2 RYAN COURTADE/BLUE ANGELS PHOTOS

As for me? I can’t begin to track what is happening. I’m tiring from repeated anti-g exertion, and these rapid-break, reverse maneuvers are disorienting.

The Low Break Cross means the Diamond again breaks apart, each Hornet heading outbound, then turning back, aimed at show-center. From the ground, it appears the four fighters are headed for the same point in space. In fact, each pilot is trusting the other three to be at their precise, predetermined altitude–or they will collide.

“Everybody flies at 375 kt. and about 150 ft. [altitude] between us,” Shortal says. “We’re all trying to meet over the middle, right on time. It’s hard to do, especially if we have winds.”

The four jets flash across at show-center–appearing to be separated by less than 150 ft., from my head-swiveling viewpoint–then break for a rendezvous behind the crowd. Shortal banks right 60 deg., pulling 7.5g briefly, unloads and reverses his bank, pulling 7.5g again and bleeding off speed. We’re joined by the two Solos and set up for the Blues’ Delta Sequence–the Delta Roll, the Fleur de Lis and Loop Break Cross.

The Roll and Cross are self-explanatory, but the Fleur de Lis is a complex, hard-to-visualize maneuver. From the Diamond, with Nos. 5 and 6 below the other four (in what’s called a “Double-V” formation), the six Hornets start a slow climb at 15 deg. nose-up. Foley calls, “Ready . . . Break!” and the two Solos roll, then push over and hold a knife-edge attitude. The Diamond performs a breakout maneuver–No. 2 pulls right and up; No. 3 goes left and up. Boss pulls straight up and Shortal does a quick aileron roll, then also pulls up. All four Diamond jets reconvene on top. The team’s smoke trails form a flower-like pattern when the maneuver’s complete.

Fortunately for the Aviation Week guy in No. 4, Shortal’s role as inflight safety officer precluded our participation in the final pre-landing maneuver, a six-Hornet formation Pull Up Break or PUB. “The PUB’s when we lose most of our backseat riders,” Shortal chuckles. “It’s a high-g maneuver–pull 8-10-deg. nose-up, then roll and pull 7.5g for 180 deg. [of turn]. The Hornet’s slick and light on fuel then, so the jet really performs well.” By breaking successively, a few seconds apart, the fighters wind up in trail on downwind, then land at 15-sec. intervals before the crowd.

HOWEVER, DURING OUR DEMO FLIGHT, No. 3 declared a minor emergency involving a landing gear indicator. Winkler and Shortal left the Delta formation and worked the problem away from the crowd, aided by MO Herbert via radio from the ground. Our visual checks of No. 3’s exterior, and Winkler’s stepping through the appropriate checklist with MO resulted in Winkler landing on an alternate runway and taking a precautionary approach-end “barrier” cable engagement. Shortal and I landed abreast of him on a parallel strip, then taxied back to the ramp as the other Blues were shutting down.

Foley later sums up the Blue Angels’ “Contract of Trust” as a deep commitment to “dispassionate analysis, a willingness to self-critique and taking ownership of an error you might have made in a particular maneuver or series. That willingness . . . develops a critical bond.

“It’s an intangible, a basic tenet that has taken on a dynamic of its own,” he continues. “It describes the way we live. And it’s more than just the Blue Angels. It’s not a stretch to say this is the way business is done [throughout] our armed forces, I think. Certainly, the Blue Angels live by the Trust and Confidence [credo] day in and day out. We rely on each other to make the right call. We’re accountable for our actions. We empower those who work for us and hold them accountable. Everything we do is built around that system of Trust and Confidence.”

Is that proven Blue Angels tenet transferable to the private sector? “If we could sprinkle a little Blue Angel dust everywhere, this would be a much better country,” Foley declares. “We don’t have the market cornered on something special, but we do have a dedication to mission. We do have that fire in the belly, that passion and willingness to say, ‘I made a mistake. How do we fix it?’ As long as we’re willing [to do that], we’re going to make progress in manifesting Trust and Confidence. And, boy; the more you have, the more you roll!”