This outstanding Politco.com article was penned by Frank Serpico, a New York Police Department detective, who refused to take part in the rampant corruption that plagues American law enforcement agencies. An excellent 1973 movie exposed NYPD corruption by graphically depicting what this courageous hero endured. To this day, outlaw cops blame Serpico for simply being an honest police officer, who takes his oath seriously.

Reprinted with permission from Frank Serpico.

William B. Scott

http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/10/the-police-are-still-out-of-control-112160_full.html?print#.VE7aP763ARk

The Police Are Still Out of Control. I should know.

By FRANK SERPICO

October 23, 2014

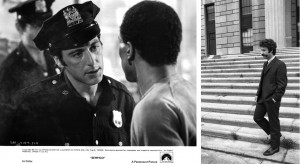

(Photo Still of Frank Serpico from Antonino D’Ambrosio’s feature documentary film Frank Serpico: Only Actions Count. Courtesy of Antonino D’Ambrosio / Gigantic Picture

In the opening scene of the 1973 movie “Serpico,” I am shot in the face—or to be more accurate, the character of Frank Serpico, played by Al Pacino, is shot in the face. Even today it’s very difficult for me to watch those scenes, which depict in a very realistic and terrifying way what actually happened to me on Feb. 3, 1971. I had recently been transferred to the Narcotics division of the New York City Police Department, and we were moving in on a drug dealer on the fourth floor of a walk-up tenement in a Hispanic section of Brooklyn. The police officer backing me up instructed me (since I spoke Spanish) to just get the apartment door open “and leave the rest to us.”

One officer was standing to my left on the landing no more than eight feet away, with his gun drawn; the other officer was to my right rear on the stairwell, also with his gun drawn. When the door opened, I pushed my way in and snapped the chain. The suspect slammed the door closed on me, wedging in my head and right shoulder and arm. I couldn’t move, but I aimed my snub-nose Smith & Wesson revolver at the perp (the movie version unfortunately goes a little Hollywood here, and has Pacino struggling and failing to raise a much-larger 9-millimeter automatic). From behind me no help came.

At that moment my anger got the better of me. I made the almost fatal mistake of taking my eye off the perp and screaming to the officer on my left: “What the hell you waiting for? Give me a hand!” I turned back to face a gun blast in my face. I had cocked my weapon and fired back at him almost in the same instant, probably as reflex action, striking him. (He was later captured.)

When I regained consciousness, I was on my back in a pool of blood trying to assess the damage from the gunshot wound in my cheek. Was this a case of small entry, big exit, as often happens with bullets? Was the back of my head missing? I heard a voice saying, “Don’ worry, you be all right, you be all right,” and when I opened my eyes I saw an old Hispanic man looking down at me like Carlos Castaneda’s Don Juan. My “backup” was nowhere in sight. They hadn’t even called for assistance—I never heard the famed “Code 1013,” meaning “Officer Down.” They didn’t call an ambulance either, I later learned; the old man did. One patrol car responded to investigate, and realizing I was a narcotics officer rushed me to a nearby hospital (one of the officers who drove me that night said, “If I knew it was him, I would have left him there to bleed to death,” I learned later).

The next time I saw my “back-up” officers was when one of them came to the hospital to bring me my watch. I said, “What the hell am I going to do with a watch? What I needed was a back-up. Where were you?” He said, “F*** you,” and left. Both my “back-ups” were later awarded medals for saving my life.

I still don’t know exactly what happened on that day. There was never any real investigation. But years later, Patrick Murphy, who was police commissioner at the time, was giving a speech at one of my alma maters, the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and I confronted him. I said, “My name is Frank Serpico, and I’ve been carrying a bullet in my head for over 35 years, and you, Mr. Murphy, are the man I hold responsible. You were the man who was brought as commissioner to take up the cause that I began — rooting out corruption. You could have protected me; instead you put me in harm’s way. What have you got to say?” He hung his head, and had no answer.

Even now, I do not know for certain why I was left trapped in that door by my fellow police officers. But the Narcotics division was rotten to the core, with many guys taking money from the very drug dealers they were supposed to bust. I had refused to take bribes and had testified against my fellow officers. Police make up a peculiar subculture in society. More often than not they have their own moral code of behavior, an “us against them” attitude, enforced by a Blue Wall of Silence. It’s their version of the Mafia’s omerta. Speak out, and you’re no longer “one of us.” You’re one of “them.” And as James Fyfe, a nationally recognized expert on the use of force, wrote in his 1993 book about this issue, Above The Law, officers who break the code sometimes won’t be helped in emergency situations, as I wasn’t.

Forty-odd years on, my story probably seems like ancient history to most people, layered over with Hollywood legend. For me it’s not, since at the age of 78 I’m still deaf in one ear and I walk with a limp and I carry fragments of the bullet near my brain. I am also, all these years later, still persona non grata in the NYPD. Never mind that, thanks to Sidney Lumet’s direction and Al Pacino’s brilliant acting, “Serpico” ranks No. 40 on the American Film Institute’s list of all-time movie heroes, or that as I travel around the country and the world, police officers often tell me they were inspired to join the force after seeing the movie at an early age.

In the NYPD that means little next to my 40-year-old heresy, as they see it. I still get hate mail from active and retired police officers. A couple of years ago after the death of David Durk — the police officer who was one of my few allies inside the department in my efforts to expose graft — the Internet message board “NYPD Rant” featured some choice messages directed at me. “Join your mentor, Rat scum!” said one. An ex-con recently related to me that a precinct captain had once said to him, “If it wasn’t for that fuckin’ Serpico, I coulda been a millionaire today.” My informer went on to say, “Frank, you don’t seem to understand, they had a well-oiled money making machine going and you came along and threw a handful of sand in the gears.”

On the left, Al Pacino plays Serpico in the 1973 movie. On the right, Frank Serpico leaves the Bronx County Courthouse after testifying on police corruption in 1973. | Getty Images

In 1971 I was awarded the Medal of Honor, the NYPD’s highest award for bravery in action, but it wasn’t for taking on an army of corrupt cops. It was most likely due to the insistence of Police Chief Sid Cooper, a rare good guy who was well aware of the murky side of the NYPD that I’d try to expose. But they handed the medal to me like an afterthought, like tossing me a pack of cigarettes. After all this time, I’ve never been given a proper certificate with my medal. And although living Medal of Honor winners are typically invited to yearly award ceremonies, I’ve only been invited once — and it was by Bernard Kerick, who ironically was the only NYPD commissioner to later serve time in prison. A few years ago, after the New York Police Museum refused my guns and other memorabilia, I loaned them to the Italian-American museum right down street from police headquarters, and they invited me to their annual dinner. I didn’t know it was planned, but the chief of police from Rome, Italy, was there, and he gave me a plaque. The New York City police officers who were there wouldn’t even look at me.

So my personal story didn’t end with the movie, or with my retirement from the force in 1972. It continues right up to this day. And the reason I’m speaking out now is that, tragically, too little has really changed since the Knapp Commission, the outside investigative panel formed by then-Mayor John Lindsay after I failed at repeated internal efforts to get the police and district attorney to investigate rampant corruption in the force. Lindsay had acted only because finally, in desperation, I went to the New York Times, which put my story on the front page. Led by Whitman Knapp, a tenacious federal judge, the commission for at least a brief moment in time supplied what has always been needed in policing: outside accountability. As a result many officers were prosecuted and many more lost their jobs. But the commission disbanded in 1972 even though I had hoped (and had so testified) that it would be made permanent.

And today the Blue Wall of Silence endures in towns and cities across America. Whistleblowers in police departments — or as I like to call them, “lamp lighters,” after Paul Revere — are still turned into permanent pariahs. The complaint I continue to hear is that when they try to bring injustice to light they are told by government officials: “We can’t afford a scandal; it would undermine public confidence in our police.” That confidence, I dare say, is already seriously undermined.

Things might have improved in some areas. The days when I served and you could get away with anything, when cops were better at accounting than at law enforcement — keeping meticulous records of the people they were shaking down, stealing drugs and money from dealers on a regular basis — all that no longer exists as systematically as it once did, though it certainly does in some places. Times have changed. It’s harder to be a venal cop these days.

But an even more serious problem — police violence — has probably grown worse, and it’s out of control for the same reason that graft once was: a lack of accountability.

I tried to be an honest cop in a force full of bribe-takers. But as I found out the hard way, police departments are useless at investigating themselves—and that’s exactly the problem facing ordinary people across the country —including perhaps, Ferguson, Missouri, which has been a lightning rod for discontent even though the circumstances under which an African-American youth, Michael Brown, was shot remain unclear.

Al Pacino in the 1973 movie Serpico. | Getty Images

Today the combination of an excess of deadly force and near-total lack of accountability is more dangerous than ever: Most cops today can pull out their weapons and fire without fear that anything will happen to them, even if they shoot someone wrongfully. All a police officer has to say is that he believes his life was in danger, and he’s typically absolved. What do you think that does to their psychology as they patrol the streets—this sense of invulnerability? The famous old saying still applies: Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. (And we still don’t know how many of these incidents occur each year; even though Congress enacted the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act 20 years ago, requiring the Justice Department to produce an annual report on “the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers,” the reports were never issued.)

It wasn’t any surprise to me that, after Michael Brown was shot dead in Ferguson, officers instinctively lined up behind Darren Wilson, the cop who allegedly killed Brown. Officer Wilson may well have had cause to fire if Brown was attacking him, as some reports suggest, but it is also possible we will never know the full truth—whether, for example, it was really necessary for Wilson to shoot Brown at least six times, killing rather than just wounding him. As they always do, the police unions closed ranks also behind the officer in question. And the district attorney (who is often totally in bed with the police and needs their votes) and city power structure can almost always be counted on to stand behind the unions.

In some ways, matters have gotten even worse. The gulf between the police and the communities they serve has grown wider. Mind you, I don’t want to say that police shouldn’t protect themselves and have access to the best equipment. Police officers have the right to defend themselves with maximum force, in cases where, say, they are taking on a barricaded felon armed with an assault weapon. But when you are dealing every day with civilians walking the streets, and you bring in armored vehicles and automatic weapons, it’s all out of proportion. It makes you feel like you’re dealing with some kind of subversive enemy. The automatic weapons and bulletproof vest may protect the officer, but they also insulate him from the very society he’s sworn to protect. All that firepower and armor puts an even greater wall between the police and society, and solidifies that “us-versus-them” feeling.

Serpico at his home in Stuyvesant, New York. | Photo Still of Frank Serpico from Antonino D’Ambrosio’s feature documentary film Frank Serpico: Only Actions Count. Courtesy of Antonino D’Ambrosio/Gigantic Pictures.

And with all due respect to today’s police officers doing their jobs, they don’t need all that stuff anyway. When I was cop I disarmed a man with three guns who had just killed someone. I was off duty and all I had was my snub-nose Smith & Wesson. I fired a warning shot, the guy ran off and I chased him down. Some police forces still maintain a high threshold for violence: I remember talking with a member of the Italian carabinieri, who are known for being very heavily armed. He took out his Beretta and showed me that it didn’t even have a magazine inside. “You know, I got to be careful,” he said. “Before I shoot somebody unjustifiably, I’m better off shooting myself.” They have standards.

In the NYPD, it used to be you’d fire two shots and then you would assess the situation. You didn’t go off like a madman and empty your magazine and reload. Today it seems these police officers just empty their guns and automatic weapons without thinking, in acts of callousness or racism. They act like they’re in shooting galleries. Today’s uncontrolled firepower, combined with a lack of good training and adequate screening of police academy candidates, has led to a devastating drop in standards.

The infamous case of Amadou Diallo in New York—who was shot 41 times in 1999 for no obvious reason—is more typical than you might think. The shooters, of course, were absolved of any wrongdoing, as they almost always are. All a policeman has to say is that “the suspect turned toward me menacingly,” and he does not have to worry about prosecution.

In a 2010 case recorded on a police camera in Seattle, John Williams, a 50-year-old traditional carver of the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations (tribes), was shot four times by police as he walked across the street with a pocketknife and a piece of cedar in his hands. He died at the scene. It’s like the Keystone Kops, but without being funny at all.

Many white Americans, indoctrinated by the ridiculous number of buddy-cop films and police-themed TV shows that Hollywood has cranked out over the decades—almost all of them portraying police as heroes—may be surprised by the continuing outbursts of anger, the protests in the street against the police that they see in inner-city environments like Ferguson. But they often don’t understand that these minority communities, in many cases, view the police as the enemy. We want to believe that cops are good guys, but let’s face it, any kid in the ghetto knows different. The poor and the disenfranchised in society don’t believe those movies; they see themselves as the victims, and they often are.

Law enforcement agencies need to eliminate those who use and abuse the power of the law as they see fit. As I said to the Knapp Commission 43 years ago, we must create an atmosphere where the crooked cop fears the honest cop, and not the other way around. An honest cop should be able to speak out against unjust or illegal behavior by fellow officers without fear of ridicule or reprisals. Those that speak out should be rewarded and respected by their superiors, not punished.

We’re not there yet.

******************

It still strikes me as odd that I’m seen as a renegade cop and unwelcome by police in the city I grew up in. Because as far back as I can remember, all I wanted to be was a member of the NYPD. Even today, I love the police life. I love the work.

Photo Still of Frank Serpico from Antonino D’Ambrosio’s feature documentary film Frank Serpico: Only Actions Count. Courtesy of Antonino D’Ambrosio/Gigantic Pictures.

I grew up in Brooklyn, and shined shoes in my father’s shop when I was a kid. My uncle was a member of the carabinieri in Italy, and when I was 13 my mother took me to see my only surviving grandparent, her father. So I met her brother the carabinieri, who was in civilian clothes but carried a Beretta sidearm. I just marveled at the respect and dignity with which he did his work, and how people respected him. My father, a World War I POW, also in his early years contemplated being a carabinieri, but he had his shoe-repair trade and became a craftsman. As a young boy I had no idea. All I knew was that I was impressed by my uncle’s behavior. This guy could open doors.

It wasn’t that I was completely naïve about what bad cops could be. As a boy of 8 or 9, returning home one evening after shining shoes on the parkway, I saw a white police officer savagely beating a frail black woman with his night stick as she lay prostrate on a parkway bench. She didn’t utter a sound. All I could hear was the thud as the wood struck her skin and bones. (I was reminded of that 70-year-old incident recently when an Internet video showed a white police officer pummeling a black woman with his gloved fist in broad daylight — have police tactics really changed?)

But I also saw the good side of cops. I saw them standing on the running board of a car they had commandeered to chase a thief. When I was a few years older, and I wounded myself with a self-made zip gun, my mother took me to the hospital and two cops showed up, demanding, “Where’s the gun?” I said I had no gun, that I’d just found a shell and when I tried to take the casing off, it exploded. They looked at me skeptically and asked me where I went to school. I said, “St. Francis Prep, and I want to be a cop just like you.” They said, “If you don’t smarten up you’ll never make it that far.” But they didn’t give me a juvenile citation, as they could have. So I knew there were good cops out there.

I wasn’t naive when I entered the force as a rookie patrolman on Sept. 11, 1959, either. I knew that some cops took traffic money, but I had no idea of the institutionalized graft, corruption and nepotism that existed and was condoned until one evening I was handed an envelope by another officer. I had no idea what was in it until I went to my car and found that it contained my share of the “nut,” as it was called (a reference to squirrels hiding their nuts; some officers buried the money in jars buried in their backyards). Still, back then I was naive enough to believe that within the system there was someone who was not aware of what was going on and, once informed, would take immediate action to correct it.

I was wrong. The first place I went was to the mayor’s department of investigation, where I was told outright I had a choice: 1) Force their hand, meaning I would be found face down in the East River; or 2) Forget about it. The rest you know, especially if you’ve seen the movie. After refusing to take money myself, but coming under relentless pressure to do so, I went successively to the inspector’s office, the mayor’s office and the district attorney. They each promised me action and didn’t deliver. The lobbying power of the police was too strong. I discovered that I was all but alone in a world of institutionalized graft, where keeping the “pad” – all the money they skimmed – meant that officers spent more time tabulating their piece of the cake more than as guardians of the peace.

Over the years, politicians who wanted to make a difference didn’t. They were too beholden to the police unions and the police vote. I wrote a letter to President Bill Clinton in 1994 addressing this very issue, saying that honest cops have never been rewarded, and maybe there ought to be a medal for them. He wrote back, but nothing changed. In New York City, then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg professed that things were going to change, but in the end he went right along with his commissioner, Ray Kelly, who was allowed to do whatever he wanted. Kelly had been a sergeant when I was on the force, and he’d known about the corruption, as did Murphy.

As for Barack Obama and his attorney general, Eric Holder, they’re giving speeches now, after Ferguson. But it’s 20 years too late. It’s the same old problem of political power talking, and it doesn’t matter that both the president and his attorney general are African-American. Corruption is color blind. Money and power corrupt, and they are color blind too.

Only a few years ago, a cop who was in the same 81st Precinct I started in, Adrian Schoolcraft, was actually taken to a psych ward and handcuffed to a gurney for six days after he tried to complain about corruption – they wanted him to keep to a quota of summonses, and he wasn’t complying. No one would have believed him except he hid a tape recorder in his room, and recorded them making their demands. Now he’s like me, an outcast.

Every time I speak out on topics of police corruption and brutality, there are inevitably critics who say that I am out of touch and that I am old enough to be the grandfather of many of the cops who are currently on the force. But I’ve kept up the struggle, working with lamp lighters to provide them with encouragement and guidance; serving as an expert witness to describe the tactics that police bureaucracies use to wear them down psychologically; testifying in support of independent boards; developing educational guidance to young minority citizens on how to respond to police officers; working with the American Civil Liberties Union to expose the abuses of stun-gun technology in prisons; and lecturing in more high schools, colleges and reform schools than I can remember. A little over a decade ago, when I was a presenter at the Top Cops Award event hosted by TV host John Walsh, several police officers came up to me, hugged me and then whispered in my ear, “I gotta talk to you.”

The sum total of all that experience can be encapsulated in a few simple rules for the future:

- Strengthen the selection process and psychological screening process for police recruits. Police departments are simply a microcosm of the greater society. If your screening standards encourage corrupt and forceful tendencies, you will end up with a larger concentration of these types of individuals;

- Provide ongoing, examples-based training and simulations.Not only telling but showingpolice officers how they are expected to behave and react is critical;

- Require community involvement from police officersso they know the districts and the individuals they are policing. This will encourage empathy and understanding;

- Enforce the laws against everyone, including police officers.When police officers do wrong, use those individuals as examples of what not to do – so that others know that this behavior will not be tolerated. And tell the police unions and detective endowment associations they need to keep their noses out of the justice system;

- Support the good guys. Honest cops who tell the truth and behave in exemplary fashion should be honored, promoted and held up as strong positive examples of what it means to be a cop;

- Last but not least, police cannot police themselves. Develop permanent, independent boards to review incidents of police corruption and brutality—and then fund them well and support them publicly. Only this can change a culture that has existed since the beginnings of the modern police department.

New York City Police Academy cadets salute during their graduation ceremony in 2013. | Getty Images

There are glimmers of hope that some of this is starting to happen, even in New York under its new mayor, Bill DeBlasio. Earlier this month DeBlasio’s commissioner, Bill Bratton—who’d previously served a term as commissioner in New York as well as police chief in Los Angeles—made a crowd of police brass squirm in discomfort when he showed a hideous video montage of police officers mistreating members of the public and said he would “aggressively seek to get those out of the department who should not be here — the brutal, the corrupt, the racist, the incompetent.” I found that very impressive. Let’s see if he follows through.

And legislators are starting to act—and perhaps to free themselves of the political power of police. In Wisconsin, after being contacted by Mike Bell — a retired Air Force officer who flew in three wars and whose son was shot to death by police after being pulled over for a DUI – I’d like to believe I helped in a successful campaign to push through the nation’s first law setting up outside review panels in cases of deaths in police custody. A New Jersey legislator has now expressed interest in pushing through a similar law.

Like the Knapp Commission in its time, they are just a start. But they are something.

Frank Serpico is a former New York City police detective.